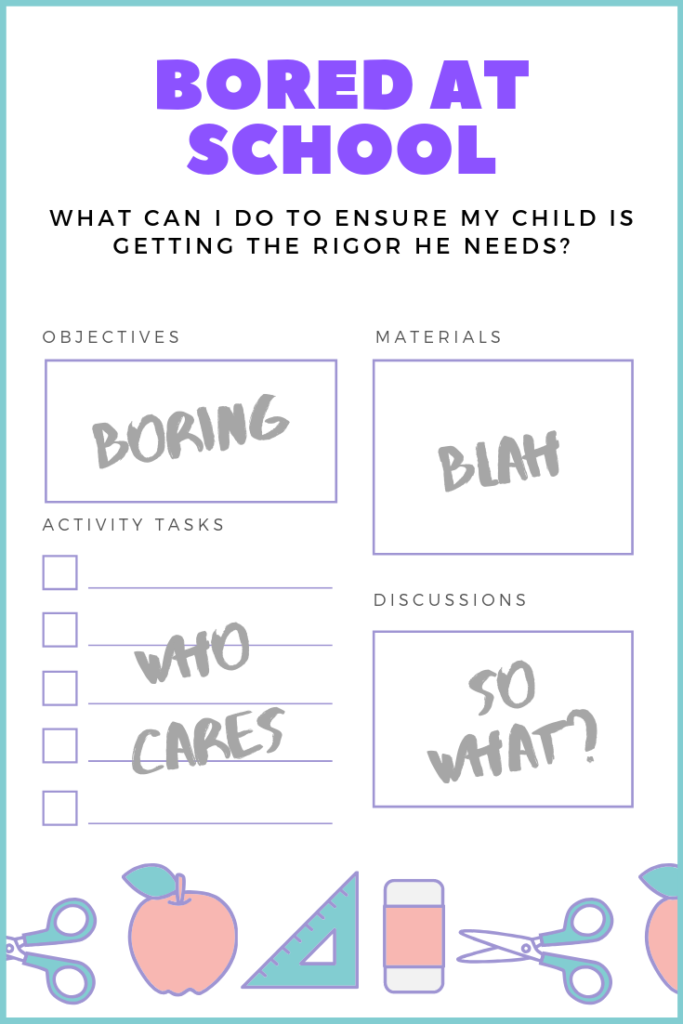

Q: When I ask my gifted child how school is each day, he almost always responds by saying this: “Really, really boring.” I’m not surprised. His math and reading skills are way above grade level, and I’m sure he just isn’t being challenged.

But, making matters worse, we’re now getting notes home from his teacher that say he’s been misbehaving in class and becoming a distraction to the other students. I think it’s just because he’s completed whatever task they were working on and has nothing else to do. What can I do to help my child and ensure he’s not bored at school and getting the rigor he needs?

It can be a struggle for teachers to meet the needs of each child

For gifted students, who pick up new skills more quickly than their peers and may even already know the material before a lesson ever begins, that can lead to frustration and being bored at school.

“Curriculum isn’t written for gifted kids,” said Dr. Michael Postma, executive director of Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted. “It’s really designed for the masses, and gifted children actually learn differently. They learn more rapidly. They learn more depth and breadth of information. And they need rigor and challenge. They need complexity in their learning. That’s how their brain is wired.”

But many teachers aren’t set up to offer gifted kids the extra instruction they need to stay focused and interested in the classroom. According to a Fordham Institute report on high-achieving students, 73% of teachers surveyed agreed that “too often, the brightest students are bored and under-challenged in school” because teachers are not giving them a “sufficient chance to thrive.”

What’s more, 65% said their education courses and teacher preparation programs offered very little or no instruction on how to help high-achieving students. And 58% said they hadn’t taken any professional development classes in recent years where they learned how to teach gifted kids.

“I don’t blame the staff or the teachers either when they’re dealing with 20 or 30 kids,” Postma said. “Sometimes it’s hard to individualize or even do flexible grouping projects on a continual basis.”

Engagement, flexibility are key

Student assessments to determine how much each child knows can be an effective way for teachers to bolster lessons, Postma said. If half of the class knows 80% of the material already, the teacher can move more quickly. “Just engaging the kids is really the key,” he said, “and so is flexibility, allowing them to go above and beyond.”

But when teachers don’t have the time or abilities to meet the accelerated needs of their gifted kids, those students can start acting out.

“Frustration leads to anger, it leads to anxiety, it leads to a lot of different psychological things,” Postma said, “and it leads to a lack of engagement and an attitude of disengagement from school, so they look for other avenues.”

That behavior, Postma said, can even result in a misdiagnosis for Attention Deficit Disorder or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder as adults try to determine why a child who seems to love to learn can’t stay focused at school.

Seek out allies

When a child complains about being bored in school, Postma recommends parents meet with school staff to find a resolution.

“Always advocate, make connections, find allies within the school district,” he said. “Maybe it’s the gifted teacher, maybe it’s the social worker or counselor. If you can work within the community, it’s always best.”

Not every teacher or school administrator, however, will be willing or able to make change within the classroom for one or two students. Just 6.7% of students were enrolled in gifted and talented programs in the United States during the 2013-14 school year, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

In those cases, Postma recommends looking for other opportunities to help gifted kids remain excited about learning. Sports, extracurricular clubs, museum visits and reading all can help gifted kids advance their own knowledge outside of the classroom and get reengaged in their own education.

But, Postma warns, parents shouldn’t have their sights solely set on academic achievement when planning their child’s extracurricular activities. Even after a boring day at school, it’s important to remember that gifted kids need some fun in their lives too.

“There are so many pressures on our kids these days, sometimes it’s OK to back off,” Postma said. “It’s OK to read for fun. It’s OK to do a video game and just chill. Our kids need to understand how to take the onus off as well.”

Visit, talk, build relationships

“The best advice for a parent is to develop a relationship—to be communicating. You don’t go and offer advice. You go and offer services and help out in the classroom. Go with words of understanding. ‘Yes, I understand you have a full classroom. Is there anyway I can help?’ Once you build relationships with staff that also gives you an avenue of also talking about other options and other venues or opportunities for the kids. Going in the other way, you quickly get the label of that parent. I always encourage building relationships first.”

Dr. Michael Postma, Executive Director of Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted

Share you own experiences

“Consider letting the teacher know what’s engaging your child and what isn’t. Often, a teacher who must deal with a large group of children doesn’t have time to think about each child’s likes and dislikes, and this information can be useful to her. The teacher may be able to give your child extra or different work that’s more exciting and fun. If the classroom has a computer, maybe the teacher will allow your child to play on it. Or perhaps she can do other tasks when she’s finished her work, such as tutoring other children or helping out in the school office. It’s important to find out what makes school interesting and fun for your child; just being given extra work, if it’s not something she enjoys, can feel like a punishment.”

Alison Ehara-Brown, Family therapist, via Babycenter.com